February 27, 2019

By Vianna Davila

When the city of Seattle set an aggressive goal to put a significant dent in the region’s homeless population — achieving 7,400 so-called exits to permanent housing in 2018 — city Councilmember Lisa Herbold assumed what many of us might: that meant 7,400 households would be moved off the streets and into homes.

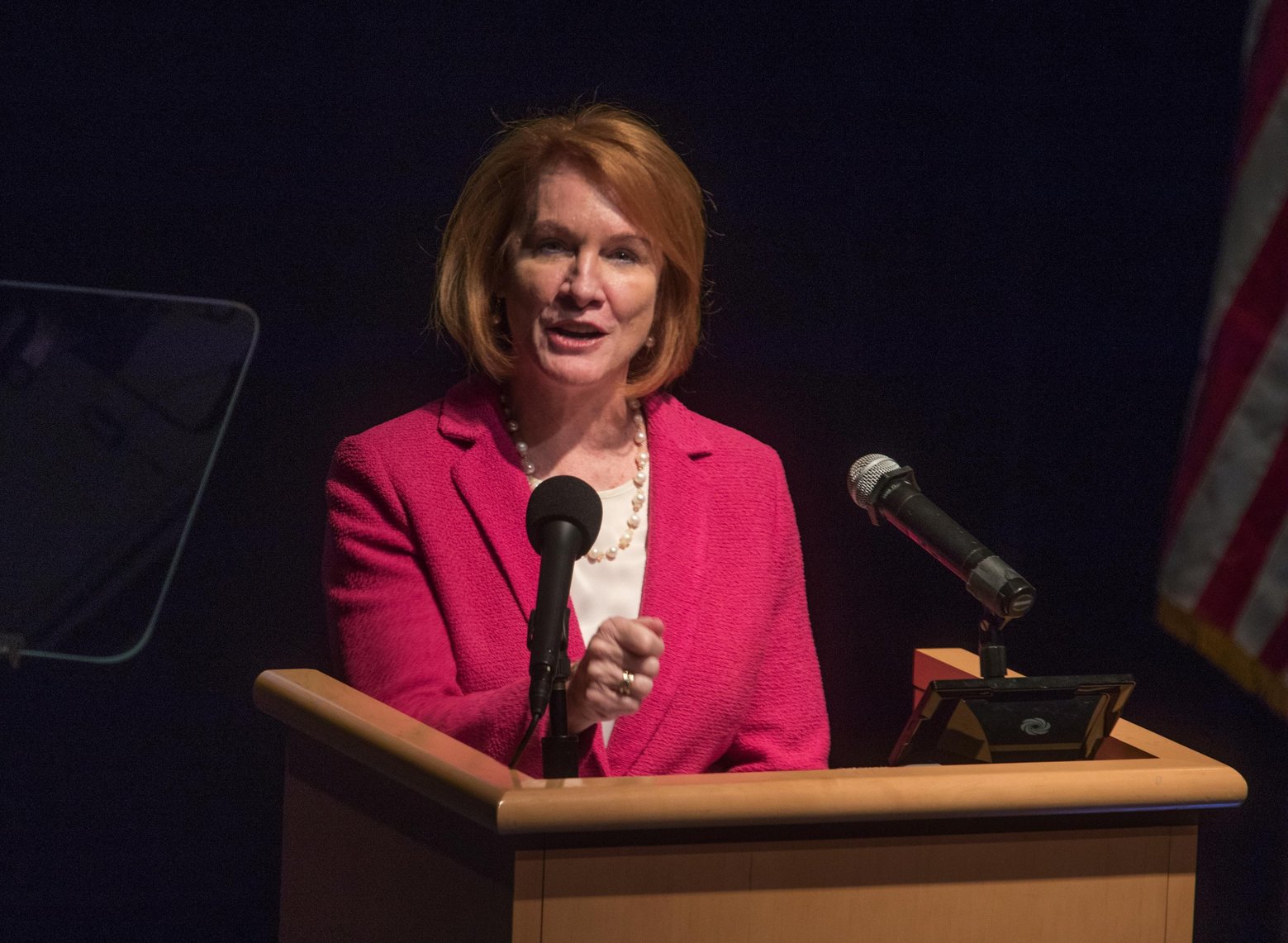

The public might have also been left with that impression had they listened to Mayor Jenny Durkan’s State of the City speech last week. “In 2018, we helped more than 7,400 households move out of homelessness and into permanent housing,” the mayor said during the Feb. 19 event.

But, as Herbold now knows, that’s not quite right.

The city did count more than 7,400 exits to permanent housing in 2018. However, that figure doesn’t refer to the number of households actually moving into homes, as city officials acknowledged this week.

The confusion over the data comes as the public continues to demand quicker fixes to a worsening homelessness crisis.

The number Durkan cited last week actually refers to the number of homeless-service programs households used — shelter, intensive outreach or housing vouchers, for example — before they got that housing. The result is that one household could be counted twice or more, depending on how many programs each utilized en route to finally securing a home, a distinction first reported on the news site The C is for Crank.

That means the city knows how well the programs it funds are doing at getting households into homes.

What the city doesn’t know, at least not yet, is how many unique households actually made it out of homelessness into housing last year.

If this sounds confusing, it is. Homeless data can be sliced many ways, depending on the questions you want answered. King County, for example, has started to look at how many episodes of homelessness occur every year.

City officials say the 7,400 target was always meant to determine how well different types of homeless programs and service providers were doing at getting people into housing, a “part of program accountability,” Human Services Department spokeswoman Meg Olberding said.

But the city also acknowledged this week that it will likely change the way they look at and present the data in the future.

Seattle still cites the number of exits as a victory — a 30 percent increase over program exits to permanent housing in 2017 — in part because of the city’s investment in more enhanced shelter beds, which have more services to help homeless people and have exit rates to permanent housing that are five times that of basic shelter.

“I look at that data, and it is enough to show me that the programs that we’re investing in are performing better than they were in 2017,” said Human Services Department Interim Director Jason Johnson.

But, he added later, the city has “some work to do to figure out what data sets help convey that story.”

Measuring success

Soon after King County Executive Dow Constantine and former Seattle Mayor Ed Murray declared a state of emergency over homelessness in 2015, Seattle shifted its focus to reducing homelessness while ensuring it was spending its money wisely.

In fall 2017, the city took a step toward that goal: they rebid $34 million in homeless-services contracts for the first time in more than a decade. As part of the process, the city set an ambitious goal of achieving 7,400 exits to permanent housing in 2018, more than double the previous target.

The city also imposed new performance measures on the organizations providing services, like outreach, shelter and prevention. Contractors agreed to achieve a certain number of exits for each program — a number that added up to 7,400.

Herbold said the council first understood about what the exit data actually means sometime around the third quarter of 2018. Among her concerns was that the 2018 exits include 1,800 households who stayed in some types of supportive housing they already had when the year started.

Herbold, still fearing the public was being left with a different impression about what an exit actually means, raised the issue with the Human Services Department (HSD) several months ago. She said they were receptive to her concerns.

“I feel like we had done some good work about being clear about what we can say and what we don’t know,” Herbold said,

So she wasn’t sure what happened with mayor’s State of the City speech. Since then, she said, the mayor’s office and HSD have worked to more accurately convey the information.

“I’m glad that the mayor’s office is straightening it out,” she said.

Understanding the data

Homelessness data lives in the county’s Homeless Management Information System, or HMIS, a federally-mandated database that tracks any time a household comes into contact with a homeless service in King County.

If Seattle wanted to know how many unduplicated households got out of homelessness last year, it would take a lot of work to parse through complex HMIS data.

However, it is possible. King County, for example, has managed to calculate unduplicated episodes of homelessness. The city also has the same access to HMIS that the county does.

The county’s data team is more robust than the city’s, said Ali Peters, data-performance and evaluation manager for Seattle’s Human Services Department. The county’s homeless-data team has been built over the past three years, while the city’s got going at the end of 2017.

Understanding the data

Homelessness data lives in the county’s Homeless Management Information System, or HMIS, a federally-mandated database that tracks any time a household comes into contact with a homeless service in King County.

If Seattle wanted to know how many unduplicated households got out of homelessness last year, it would take a lot of work to parse through complex HMIS data.

However, it is possible. King County, for example, has managed to calculate unduplicated episodes of homelessness. The city also has the same access to HMIS that the county does.

The county’s data team is more robust than the city’s, said Ali Peters, data-performance and evaluation manager for Seattle’s Human Services Department. The county’s homeless-data team has been built over the past three years, while the city’s got going at the end of 2017.

Durkan and her Human Services Department acknowledged that the data system has significant limitations. She also would prefer to track homelessness by individuals, rather than the county’s method of focusing on households.

“One of the things that’s been most frustrating to me as mayor is that our data system is not only imperfect, but it starts to get in the way of our ability to solve the problem,” Durkan said Monday.

And the mayor, and others, believe the data analysis is further complicated by the fact that no single entity oversees homelessness in the region. That could change soon. Durkan and King County Executive Dow Constantine in December endorsed a merger of their current homeless services, which are now spread across six different entities.

“We need to have one system in place that also improves the data we are collecting so that we know exactly who is experiencing homelessness, what services they need and what progress we are making by individual,” Durkan said.

To read the full story, visit https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/homeless/how-many-people-escaped-homelessness-last-year-seattle-doesnt-know/